Unknown Treasures of the Collection

Like the small, white tendrils of mycelium reaching across the landscape underfoot, knowledge similarly spreads through networks that we can't always see. Mycelium is the vegetative component of a fungus, branching out among the forest floor or perhaps a rotting log to produce fruiting bodies in the form of a mushroom. The reason I present this poor analogy is because I felt particularly affected the other day by the lingering knowledge carried by our first Director--and in this case, it came in the form of mushrooms.

|

| Sarcodon imbricatus, a widely distributed "hedgehog" mushroom associated with conifers. |

Lois Nestel's many years spent probing the local landscape resulted in a wealth of practical knowledge, illustrated through her many projects that are now part of the Museum's permanent collection. Much of her work is already displayed for visitors, from taxidermy specimens to acrylic paintings of you guessed it--mushrooms. There are more of her creations in this building than meets the eye, though. I recently became acquainted with a hidden, and hefty collection of her work--numerous pages of illustrations that detail local plants, mushrooms, and phenology.

|

| Framed paintings of local mushroom species hang in one the Museum's hallways. |

With 36 pages of annotated mushroom illustrations, Lois painted the natural world as she understood it many years ago. What we now have is a record to compare how this world has changed since then. Knowing some about local mushrooms myself, I was immediately curious to see which of these species were categorized differently today. So, I looked up each of the 80 named mushrooms and discovered that the taxonomy has changed for 18 species.Why does this matter? Using context clues such as this, I could glean a bit more from these largely undocumented illustrations. Perhaps with an adequate amount of time and interest, the latter of which I have plenty of, I might narrow down the years that these illustrations were produced based on terminology used.

|

| Above, various "Bolete" mushrooms of the Boletus and Suillus genera. Below, Geastrum triplex and other unidentified species. |

Additionally, Lois left us with 16 pages of herbarium and fungus illustrations on large notebook pages. I was delighted to see familiar plants that live in our area today, and of which Lois has written about in her wild foods manuscripts. Staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina), lambsquarters or pigweed (Chenopodium album), and mullein (Verbascum thapsus) are just a few. What impresses me most about this work is that I know Lois didn't simply copy pages out of a book--she truly lived her work and surely foraged for these plants on a regular basis right in Cable.

|

| Clockwise from the top left: hawthorn, black haw, staghorn sumac, rose, marsh marigold, and highbush cranberry. |

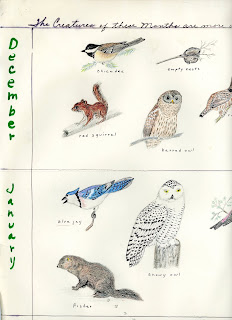

Lastly, I'd like to mention what Lois has left us for the study of phenology. Phenology in a very basic sense is a study of time. It is our understanding of periodic events that take place in the natural world where we live--when blueberries ripen or when chipmunks begin to gather nesting material. In an additional collection of illustrations, Lois noted when certain events took place here by the week for each month of the year. And so again, she left us a record of a particular place in time.

|

| A snippet of generalized winter events, in which Lois notes "the creatures of these months are more or less interchangeable," in fading ink. |

I like to think that the Museum has always celebrated Lois, and will continue to do so as long as our institution exists. She has added so much to our collective knowledge, even when it wasn't intentional. I look forward to discovering new treasures and small signs of her knowledge continuing to spread in our community.